Rolling Back Escalante National Monument: The Impacts to the Packrafting Community

Recent Efforts by President Trump and Utah’s Representatives Could Impact Access to One of the Lower 48’s Premier Wild Packrafting Landscapes

March 23, 2018 update:

Photos, video, and story by Dan Ransom

While Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument’s scenery is every bit as impressive as its five more famous national park siblings, what makes it so special is its primitive, undeveloped character. Since its designation as a National Monument in 1996, this area (also known as simply Escalante National Monument) is required to be managed primarily for conservation, low-impact recreation, and limited development. This makes for a fundamentally different type of recreational experience, one with very few paved roads, smaller crowds, and almost no developed infrastructure. There is no doubt the Escalante area is one of the premier packrafting landscapes for backcountry boating in the United States. current management plan

paving the way (pun intended) to lay concrete across 40 miles of Hole in the Rock Road and to deny significant public input for management of the new National Park they propose. This blog post looks at the history of the area and explains the potential results of these actions and offers some options for how packrafters can make their voices heard. The BLM comment period ends Monday, March 19 (Click here to comment now).

Unpaved Roads, River Willow Jungles, and Remote Canyons

I’d been warned of an unpaved road so thoroughly destroyed by washboard; there was no way the pizza-cutter wheels on my 1995 Honda Civic could survive more than a few miles. I rallied south off Highway 12, and 25 teeth-chattering miles later, I finally parked above the Dry Fork of Coyote Gulch, on my way to explore the famous Peek-a-boo and Spooky slot canyons.

For a kid who grew up in Salt Lake, my early trips to Southern Utah almost exclusively meant visiting one of the Mighty Five National Parks. Escalante was a totally new experience for me. Here was a place every bit as impressive as Zion or Arches, but at the same time totally different. Instead of navigating bumper-to-bumper traffic and viewpoints choked with tour busses, we had miles of unpaved roads only interrupted by the occasional slow-moving cow. It felt like I had stumbled off the edge of the radar and discovered something special. Little did I know those Dry Fork slots were just a tiny sliver of the hundreds of canyons that would draw me back to Escalante dozens of times searching for technical canyoneering routes.

Much of the year, the only way to access these canyons is through complex route-finding or bushwacking close to the river. The canyon floor is a jungle of willows, cottonwoods, and box canyons that hides her secrets well—it takes some serious time and effort to unlock.

But on above average snow-years, this magical thing happens. This tiny desert river swells with runoff and suddenly traversing the Escalante River becomes a simple, elegant floating adventure that feels like cheating.

The window to float the Escalante is notoriously fickle—sometimes only opening up for a handful of days at a time. But when conditions line up, it is undoubtedly the most enjoyable way to see the backcountry. The combination of length, scenery, and wilderness qualities makes for one of the best backcountry packrafting experiences in the Lower 48.

Escalante Packrafting – As the Water Drops, the Stoke Rises from Dan Ransom.

Unfortunately, the current access packrafters, canyoneers, and other explorers enjoy is now in jeopardy. Why?

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument: A Brief History

The Original Designation

On September 18, 1996, President Bill Clinton established Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument under the authority of the 1906 Antiquities Act to protect the extensive natural and human history resources of the area. The original monument was 1.9 million acres of terraces and plateaus, multi-hued cliffs, and winding canyons and river bottom. To obtain a solid swath of the landscape with no inholdings the Federal Government negotiated a land transfer with the State of Utah for approximately 180,000 acres and purchased outstanding coal leases to eliminate potential future threats of industrial development within the Monument boundaries. The Bureau of Land Management developed the current management plan, and it has been in effect since February 2000.

The Rollback Presidential Proclamation

On December 4, 2017, President Trump issued Proclamation 9682 to dismember the 20-year-old Monument and replace it with three, much smaller units covering about half the acreage of the original Monument. The legality of this proclamation is widely contested and is currently being challenged in court. These cases will likely take years to work their way through the judicial system for a final ruling.

In the meantime, the boundary reduction requires the BLM to rewrite the existing monument management plan. That plan has been in effect for nearly 20 years and is generally favorable for packraft access and backcountry permits. A new plan could potentially diminish packraft access, create additional permitting requirements, and minimize the public’s input in the planning stages.

Utah’s Politician’s So-Called “National Park”

To add a wrinkle of complexity, the fate of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument does not lie exclusively with the judiciary. In order to avoid a potentially unfavorable court ruling, Representative Chris Stewart (UT-02) introduced HR4558, which, if passed, would establish the Escalante Canyons National Park and Preserve. National Parks may only be created through acts of Congress, and are traditionally managed at the federal level by the Department of the Interior.

A new national park sounds great, but the devil is in the details: HR4558 specifies a unique land management approach for this particular National Park that would hand all decision making and control to a select group of Utah County Commissioners. Further, the bill will transfer ownership of Hole in the Rock Road to the State, so that it can be paved in preparation for a state park to be built, overlooking Lake Powell. Removing monument protections from this corridor allows the state to circumvent the current 12-person group size limits, pave the road, and potentially develop infrastructure such as a visitor center.

The boundary reductions also re-opens the door to coal mining operations on the Kaiparowits and the construction of the Lake Powell Pipeline along the southern section of the original monument boundaries.

So What Does This All Mean? (Differences in Land Management Policies & How They Affect Packrafters)

To understand differences in management plans and what real-world impact they have on the ground, it helps to understand the patchwork quilt of land designations that are in play. There are five main designations to consider: Common BLM Rangeland, National Monument, Wilderness Study Areas, National Recreation Area and National Park Each of these designations has specific management mandates.

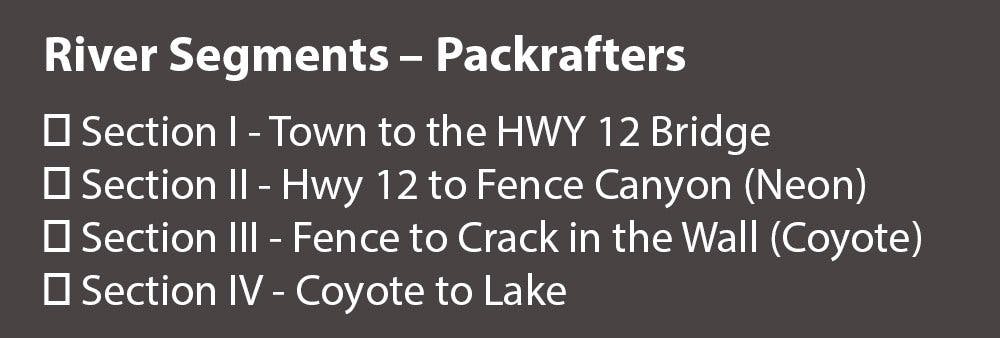

The Escalante River itself courses through a handful of different land designations as it winds its way through the area. There are four sections of packraftable river, with sections II and III being the most popular (see Sidebar). A change in the land designations for the river corridor can affect paddling access.

Common BLM Rangeland

Prior to designation in 1996, most of the monument area was Common BLM Rangeland, which was managed under a multiple-use mandate. Basically, this mandate requires land managers to balance the competing interest of conservation, recreation, and industry.

National Monument

The National Monument management plan for rangeland effective as of February 2000 differs from common BLM rangeland management in one meaningful way; it prioritizes conservation while restricting development. Specifically it:

- Limits rangeland improvement for cattle, including pinyon/juniper removal, planting grasses and forage, and water source improvements;

- Prohibits paving or modifying surfaces of existing roads (like Hole in the Rock Road);

- Prohibits future mining operations;

- Limits group sizes to 12 people.

Both the presidential proclamation and Rep. Chris Stewart’s HR4558 roll back monument designations to common BLM rangeland. Should either the President or Rep. Stewart prevail, the Monument would likely lose much of its wildness. Groups of larger sizes would be allowed, and there would no longer be a vast, remote wilderness packrafting landscape in Southwest Utah.

Wilderness Study Areas

Within the Monument are 14 Wilderness Study Areas (WSA). A WSA is land that has been inventoried for permanent Wilderness protection, but has not yet been designated by Congress. In short, these are lands with the most outstanding scenic and wilderness qualities in our nation’s public lands portfolio, and they are prioritized for protection explicitly to preserve these characteristics. These designations are temporary until Congress either permanently designates them as Wilderness or removes them from the WSA inventory.

The most obvious area omitted from the President’s and Utah Representative’s revised boundaries is the Scorpion Wilderness Study Area, which is immediately along the Hole in the Rock corridor and includes the Egypt canyon complex and the Dry Fork Coyote canyon complex. These canyons are popular for technical canyoneers, and Twentyfive Mile Wash serves as an access point to the Escalante River for packrafters. The remote nature of these areas, and their protected status could be compromised should the President or Utah’s legislation prevail, as it would put this fragile area back into only a temporarily protected status.

National Recreation Area – Glen Canyon

All of section III and section IV of the Escalante River fall within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The most significant potential change in Glen Canyon would be the sale or long-term lease of the lands at Hole in the Rock to the State of Utah. It is likely the land would be used to build a State Park with a visitor center and other services. This area is 40 miles down the Hole in the Rock Road, and adding visitor services and/or paving the road would have significant implications for increased backcountry visitors to Coyote Gulch, Fortymile, and Willow Canyons—all popular access points for packrafters. This stretch is already one of the most popular areas in the entire Monument, and is the main access point to the lower Escalante for packrafters. Increased crowds and use could result in a more rigid permitting process for the stretch of river passing through the National Recreation Area.

– HR4558

No section of HR4558 deserves more scrutiny then the language that designates a new National Park. The bill has no map, so we know very little about the boundaries of this proposed park, other than it is estimated to be around 100,000 acres. Most likely, this will focus on the area around Highway 12, Calf Creek, and the Hogback, including the most popular entry point for packrafters at the Highway 12 bridge.

A National Park could be a wonderful idea if it came with a management plan that furthered the National Park Service’s mission to protect and preserve parks for future generations. But in this case, the devil is in the details. This is not a National Park in any traditional sense of the word. In fact, it would not be managed by the National Park Service at all. The park would be managed exclusively by a Management Council dominated by state and county representatives. The National Park would be required to implement Management Council decisions, including specific language to graze cattle in perpetuity and no restrictions on hunting. This kind of management arrangement doesn’t exist anywhere else in the National Park system. In essence, American taxpayers will fund the National Park, but county officials will decide how it’s run and whom will benefit.

Most importantly, this Management Council could minimize public input on this portion of our public lands, including the input of packrafters.

What You Can Do

As a community, is vitally important we make our voices heard. How?

- Write a Note.Tell the BLM what you think during the public comment period that ends March 19th.

- Make a Call. As of March 5, 2018, HR4558 has still not been ordered reported, which means it has not passed through committee before being sent to the entire House. Consider calling your congressman to voice your opinion about what should happen to your National Monument.

- Stay informed. You will find updates on the lawsuit challenging President Trumps proclamation on the Grand Staircase Escalante Partners Website.