In far Northwest Australia lies a vast wilderness of palm-clad tablelands and spinifex*-covered plains carved by seasonal rivers. About the size of California but with a thousandth of its population, the Kimberley hosts marginal, million-acre cattle stations, isolated Aboriginal communities and national parks accessible only by helicopter. In 2018, a Brit and Kiwi explored the region’s Fitzroy River by packraft.

Photos and story by Chris Scott. To read more about Chris and Jeff Condon’s adventures, visit Inflatable Kayaks & Packrafts.

Only one track, the notorious car-killing Gibb River Road, bisects the entire region of the Kimberly from west to east. But, land access is only possible half the year.

Even mining has had little impact here – and by the standards of mineral-rich Western Australia, that says a lot. No one wants to see it end up like the Pilbara, 600 miles to the southwest, criss-crossed with private railroads and pitted by huge, open cast excavations.

Where Water Abounds

The Kimberley abounds in one resource Australia desperately needs: water. Every summer the temperatures and humidity climb until a monsoon spins off the equator to dump huge volumes of rain which spills quickly back into the Timor Sea.

The Kimberley is just too far from Australia’s drought-struck population centers to make a pipeline viable. I revisited this area eagerly as a guidebook writer, often spending too much time, fuel, and money researching out-of-the-way spots that ended up as just a line or two in the finished book.

And all along I knew I’d barely scratched the surface and my work there left me wanting to get deeper. Follow a river – that would be the way to do it. With average daytime temperatures exceeding 90°F, all hydration and load-carrying needs were eased.

Most of the big Kimberley rivers, the Durack, Drysdale, and King Edward, drain north into the Timor Sea, lapping a desolate, fjord-riddled coastline. But factor in 35-foot tides, saltwater crocs, plus the need for a sketchy float plane pick-up, and this was no place to be trapped on mile-wide mudflats.

While paddling cumbersome sea kayaks, the late Australian adventurer, Malcolm Douglas, explored this landscape in the early 90s. He found an amenable, croc-free stretch of river with attainable access and exit points. I knew that no matter how easy you made it: the coolest period, the flattest river or the fewest obstacles – the harsh reality of the Kimberley would take its toll.

Packrafting Country

We decided to do the 500-mile Fitzroy, the Kimberley’s longest river. At peak flood it runs at 30,000 cfs past the isolated community of Fitzroy Crossing on Highway 1. To Jeff and I, that sort of flow sounded too much like the aftermath of a Dambusters’ raid. We decided September, the end of the Dry, would make an easier introduction.

Cooler and less humid, we’d just have to prepare to tramp the sandbanks, rock jams, and debris-clogged channels between the pools.

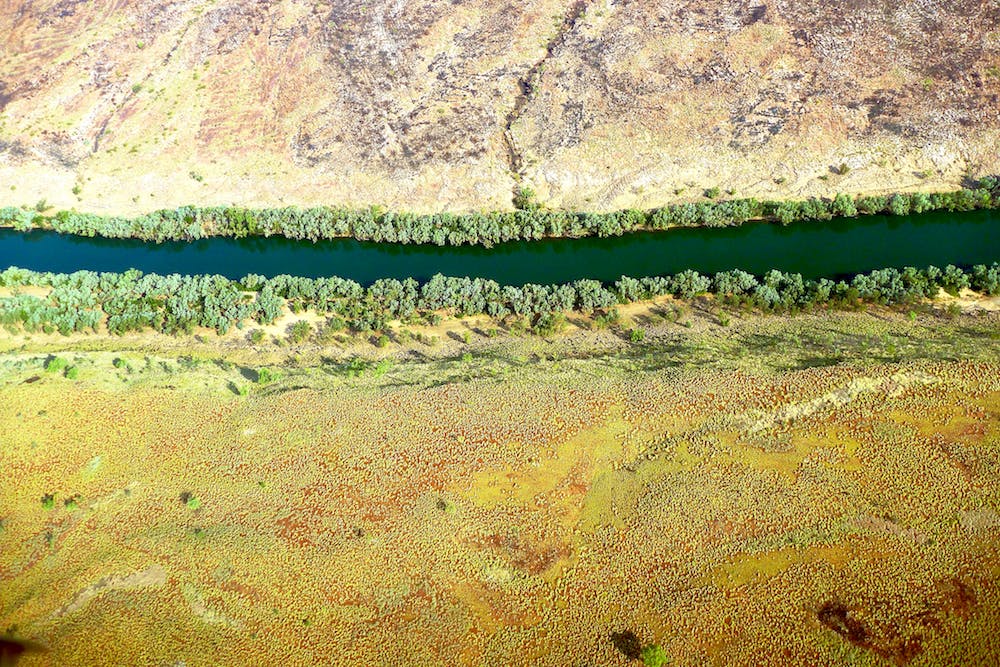

“A Lot more water down there than I expected!” shouted Jeff over the din of the Cessna. “It’s gonna be good!”

We were tracking the Fitzroy upriver – a rough, full-day’s drive reduced to a 30-minute flight. Two thousand feet below and against our expectations, the river looked 80% paddleable. There’d be a lot less walking and wading than we’d anticipated.

We touched down at a remote eco lodge, whose owner agreed to drop us off at the river next morning, 85 miles from Fitzroy Crossing. But unlike myself, experienced kayaker, Jeff, had yet to won over by Alpackas. Instead he’d be paddling a pool toy.

“It floats; it’s light and it’s cheap. It’ll do the job,” Jeff claimed.

But, by the end of that day – a long hack into the hot wind – he wasn’t so sure. Though it was only a little slower than my Yak, it took twice the effort to shift, no matter what you tried. Paddling his soggy water-sofa burned him out.

Into the Leopold Ranges

On the water soon after dawn, by the mid-morning next day we glided through Dimond Gorge, marking the southern edge of the Leopold Ranges.

Ahead of us lay cattle country where we expected the river to lose its definition as it meandered past granite outcrops towards the highway bridge. Sure enough, after lunch the flow dissipated into a gnarly rock bar where an arduous portage over car-sized boulders left me croaking with thirst. Out here, walking consumed so much more energy than paddling.

But although we’d end most days exhausted, the cattle plains turned out to be the highlight. Frequently the river’s main channel got choked with flood-borne sand, pushing the flow into the trees alongside the banks. Here, under a cool canopy of river gums replete with twittering of birds, we’d wade the sandy shallows for hours, towing our rafts like sleds.

Occasionally we squeezed under or climbed over a log jam, or sank to our thighs in quick sands. Jeff nursed his the slackraft, repairing punctures almost daily. The feral cattle and harmless freshwater crocs (a species unique to northern Australia) usually scuttled away or stared indifferently as we sploshed by.

From just before dawn until sunset, the bush resonated with avian chattering, from the strident squawks of corellas, cockatoos, and kookaburras, to the plangent coo-ing of the crested pigeons. It became the soundtrack for our six-day descent to the bridge.

Come the evening, we’d spread out on a sandbank with plentiful firewood in arm’s reach, and set about reviving ourselves from the day’s labors.

On the fifth day we sighted the Geikie Ranges, the northern gateway to an unbroken, channel that flowed past the distinctive ramparts of Geikie Gorge National Park, back on the fringes of civilization. Eons of flooding had eroded the former limestone reef into bizarre, scalloped forms.

Freshwater crocs laid their eggs on the scorched sandbanks opposite, while out in the 100-degree heat, we pushed on into the twilight to complete a marathon 12-hour, 20-mile day. The following afternoon we crawled up the steep bank below the Fitzroy highway bridge, sun burned, shriveled and sore. Jeff left his patched-up slackraft with a delighted aboriginal kid. Me, I had plenty of adventuring still left in my Yak.

*Spinifex is a genus of perennial coastal plants in the grass family.